7 Properties of Trauma Memories

Most of what we experience doesn't leave a lasting trace in your memory. Learning and remembering new information often requires a lot of effort and repetition. Consider the last time you needed to retain information for a tough exam or master new tasks for your job. It's easy to forget what we've learned or an inconsequential experience.

But some experiences can haunt us for years. Life-threatening events — things like narrowly escaping from a fire or a horrific traffic crash — can be impossible to forget, even if you try.

People who have experienced trauma report a wide range of distressing symptoms, many of which are related to the properties of their trauma memories. Understanding these memories' properties can help normalize their experiences, reduce catastrophic appraisals of their memory symptoms (e.g., "I'm going mad"), and prepare them to process these traumatic memories.

Important properties of trauma memories include:

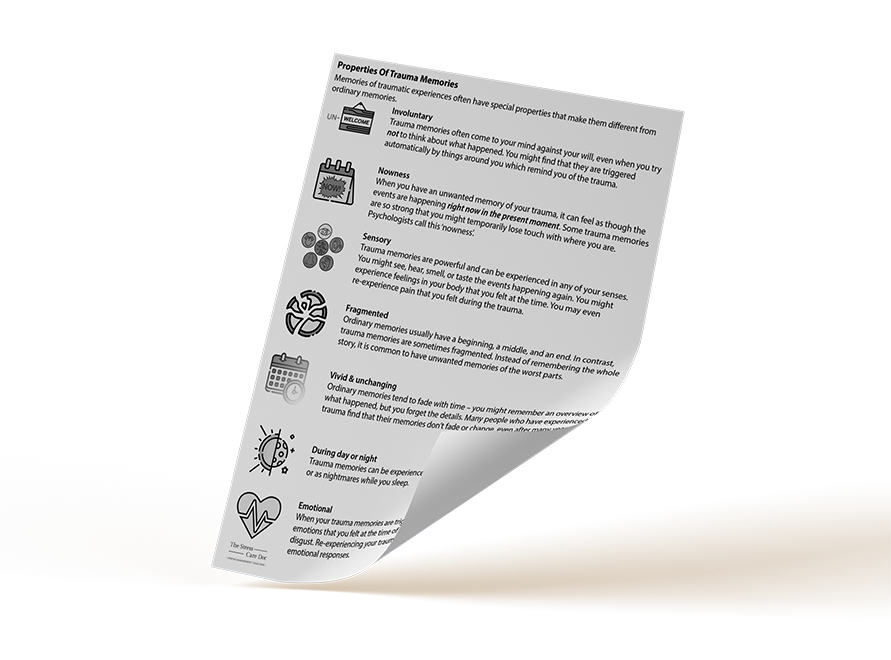

- Involuntary recall. Although ordinary memories can be subject to involuntary recall, trauma memories are often deliberately avoided and are more likely to be re-experienced involuntarily. This is partly maintained by the way that trauma memories have been encoded and stored, which makes them prone to involuntary recall as a result of perceptual cues that resemble those present at the time of the trauma (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), and partly due to the individual's attempts to suppress their memories which can lead to an unintended rebound effect (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Wegner, 1994).

- Nowness: A sense of the traumatic event happening in the present moment. Unwanted memories of a trauma exist on a continuum, from knowing that the event happened in the past to feeling as though it is happening again in the present moment. Unlike standard (episodic) memories, stronger versions of re-experiencing are not accompanied by an awareness that the content of the memory is a past event (Ehlers, Hackmann & Michael, 2004). The word 'nowness' is sometimes used to describe this phenomenon (Brewin, 2015; Ehlers, Hackmann & Michael, 2004). 'Nowness' is observed in children with PTSD (McKinnon, Nixon & Brewer, 2008) and is a property that distinguishes involuntary memory in PTSD from the kinds of involuntary memories reported by people who are depressed (Birrer, Michael & Munsch, 2007; Reynolds & Brewin, 1998).

- Predominance of sensory representations. People suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder frequently report that the sensory aspects of their memories are very distressing. For example, they might report seeing an unpleasant expression that was on the face of their attacker, hearing sounds that were present at the time of their road traffic accident, or smelling the deodorant that their attacker wore. The sensory aspects of the memory are sometimes experienced in the absence of other parts of the memory' story' (Van Der Kolk, 1994; Ehlers & Steil, 1995; Ehlers, Hackmann & Michael, 2004). There is emerging evidence that some individuals with PTSD who experienced pain at the time of their trauma experience the same pain in the form of flashbacks when reminded of their trauma (McDonald et al., 2018; Whalley, Farmer & Brewin, 2007).

- Fragmentation. Some accounts of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have reported that when people who have experienced trauma are asked to describe what happened to them, their narrative can be 'fragmented.' Evidence regarding the fragmentation of narratives is somewhat contentious (e.g., Rubin et al., 2016; Bedard-Gilligan, Zoellner & Feeny, 2017), but there is some evidence supporting the fragmentation position (Brewin et al., 2016). This fragmentation can be in the form of missing parts of the narrative or difficulty in describing it verbally, affecting a person's appraisal of an event. For example, someone could be ashamed of how they acted during a traumatic event because they do not recall how they were coerced to do so (Ehlers, Hackmann & Michael, 2004).

- Vividness and immutability. Trauma memories can be startlingly clear, even many years after the event – in a dissociative flashback, the person may even lose all awareness of their present surroundings (Blix et al, 2020; Ehlers, Hackmann & Michael, 2004). Intrusive trauma memories are 'unchanging' in that they fail to incorporate new information. For example, the perpetrator might have died since the event, but this is not reflected in the memory (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), or the client may feel a strong sense of guilt, despite having subsequently discovered that they weren't to blame (Ehlers, Hackmann & Michael, 2004).

- Re-experienced during the day or night. During the day, trauma memories can be experienced as flashbacks or unwanted memories. While asleep, traumatic memories – or themes associated with them – may be retrieved and re-experienced in the form of nightmares.

- High levels of emotion. Trauma memories are often accompanied by high levels of emotion. This might include replays of emotions that were felt at the time of the trauma (e.g., feeling paralyzed with fear when I have a flashback) or emotions accompanying post-traumatic appraisals (e.g., a sense of shame when I think "I should have fought back"). These emotional reactions can also be observed in the phenomenon of "affect without recollection," wherein an individual may re-experience emotions relating to a traumatic event without recalling it (Ehlers & Clark, 2000).

Under normal circumstances, sensory aspects of a memory (e.g., sights, sounds, smells) and contextual aspects (e.g., time, place, situation, context) would be encoded at the same time and stored as a coherent memory. However, during the heightened emotion of a trauma, the brain regions which process memory – particularly the hippocampus – do not operate as effectively. The hippocampus usually 'stitches together' memories, but irregular hippocampal function prevents memories from being properly placed into context. As a result, the sensory and contextual aspects of an event are stored incorrectly, leading to them being re-experienced. (Brewin, Gregory, Lipton, Burgess, 2010).

Properties Of Trauma Memories is an illustrated information handout that describes these unique aspects of trauma memory. It is designed to help clients and therapists explore experiences of their trauma memories.

Begin processing your trauma memories with the help of this handout.